BY: STEVE HENSHAW

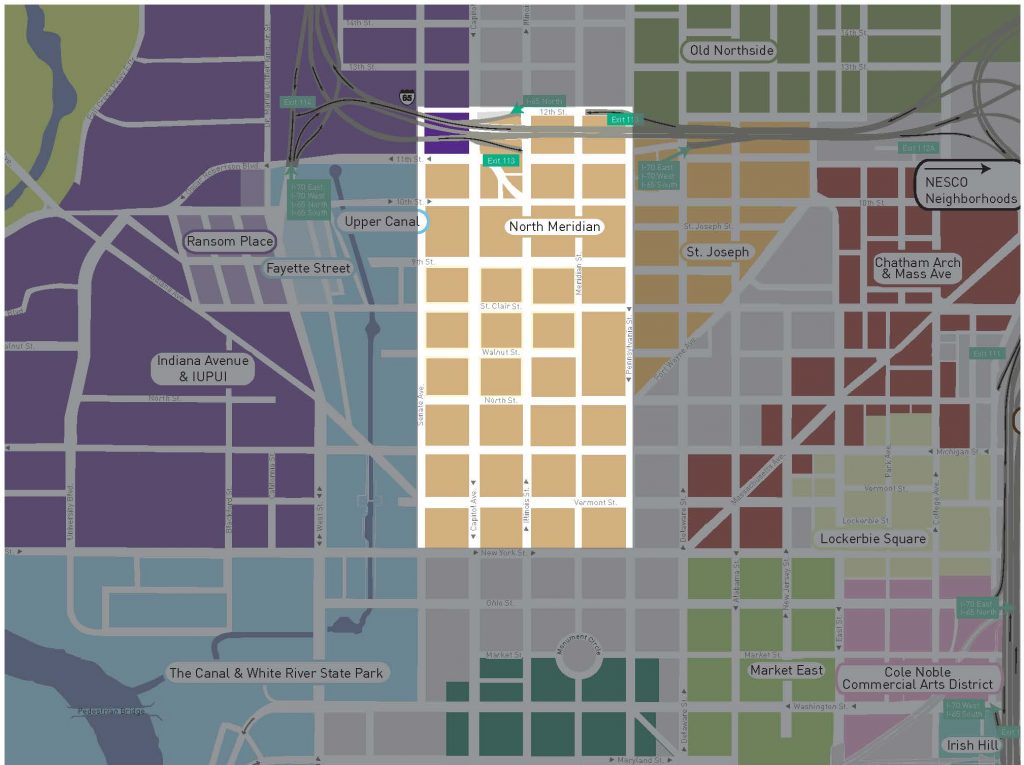

Metropolitan cities across America have experienced a renaissance over the past 15 to 20 years with new construction and development of Brownfields, and nowhere is this more prevalent than in the City of Indianapolis. Laid out in a grid, Indianapolis is partitioned into sections and intersected by freeways like spokes on a wheel — creating the “Crossroads of America.”

Over the years, patches of each quadrant have seen a slow, deliberate wave of redevelopment and revitalization wash over it. Factories have been replaced with luxury apartments and hotels, warehouses have been transformed into office buildings and craft breweries and old garages are getting second lives as art galleries, restaurants and grocery stores. These buildings are a natural fit for adaptive reuse with their large footprints and timeless architectural features and their redevelopment brings commerce and excitement to distressed areas. The biggest hurdle standing in the way of most of these revitalization efforts is potential environmental hazards left behind from years of industrial operation. We manage environmental cleanups to revitalize these properties all the time. It’s what we do for our clients every day. But, in this particular case, it’s what we did for ourselves and for the surrounding North Meridian Neighborhood in Indianapolis.

Brownfields Site History: An Old Transmissions Garage

The 825 N. Capitol building operated as a transmission and automotive repair shop for decades and it sits on a stretch of Capitol Avenue just a few blocks north of the Indiana Statehouse, and right across the street from the famous Litho Press Building, now a luxury apartment complex. We originally purchased the building to store our equipment and company trucks. In a few short months, we found ourselves needing more space for our employees and we decided to use the space to build a new corporate headquarters.

The unassuming cinder-block structure with a limestone façade was first constructed in the 1930s and because it operated as an auto repair shop, there were unexpected spills and releases of oils and solvents that found their way into the soil and groundwater. In addition to specific source contamination, groundwater beneath the building was also impacted from an unknown upgradient source.

Seeing the Brownfields Site Potential for Redevelopment

In 2000, EnviroForensics opened its Indianapolis office with three people in the old Stutz Auto Building, which is the “original” Indianapolis Brownfield Redevelopment, made up of nearly 100 offices and art studios of various size and configuration. By 2010, the office grew in size and was relocated to another old warehouse at 602 N. Capitol, above an active dry cleaner. As the city downtown grew and parking became more scarce, management found an old automotive repair company at 825 N. Capitol Ave. to store its trucks and equipment. By 2016, EnviroForensics was bursting at the seams with staff jammed in the main office and several satellite offices located in nearby buildings. By this time, EnviroForensics had grown to over 60 people and it was pretty clear that they needed to consolidate the team and find a new office space. After assessing the financial implications of renting more office space and committing to a new lease, it became clear that the old automotive repair building could be remediated and refurbished as the corporate headquarters.

“We wanted to make a statement with our headquarters about conservation, reuse and giving back to the community. Not only did we want to create a great environment for our team to work in, we wanted to reuse a structure that had once been a thriving part of the local economy and assist the neighborhood in maintaining its industrial legacy and heritage.”

Rising to the Redevelopment Challenge

The 825 N. Capitol Avenue property needed serious updates. Not only was the building divided into separate structures, old and in disrepair, but in order to get financing from the bank for the construction build out the soil and groundwater quality beneath the building needed to be assessed and remediated and the employees occupying the new building needed to be protected from potentially harmful vapors emanating from the soil and groundwater beneath the building. From a construction standpoint, the property had many issues, which included:

Redeveloping Our Brownfields Site With Insurance Archeology

For us, dealing with the environmental issues was relatively painless, as we conducted the research of the historical operations and we were able to find the old Commercial General Liability (CGL) policies of the past owners and operators. Because the soil and groundwater was contaminated, the Indiana Department of Environmental Management demanded that the site be fully assessed and understood and that soil vapors be routed from beneath the subsurface concrete slab to the roof line, so they did not build up and create an indoor health hazard. In tendering the insurance carriers of the former owners and operators, we were able to get the old insurance carriers to pay for all of the environmental and legal costs required to get the building squared away from an environmental standard and satisfy the banks concerns regarding the soil and groundwater contamination.

To learn more about how CGL policies can work for you, read How Does It Work? Insurance Archeology and CGL Policies.

While remediation efforts were ongoing, we contracted Brandt Construction and Mawr Architecture and Interior Design to start work on shoring up the structural integrity of the building, and designing the eventual floor plan, so we could push the project forward as quickly as possible. The Brandt crew turned the two buildings into one by:

With the electric and water utilities installed, the skeletons of office walls put up, and the windows replaced, the bones of our building were complete.

Bringing Further Revitalization to the North Meridian Neighborhood

The new and improved EnviroForensics building is now a two story, 23,000 square foot office and community space with beautiful exposed brick walls, stylish edison bulb light fixtures, and plate glass room dividers.

The hallways are a celebration of Indiana artists with work from 13 Hoosier painters and photographers. We’re proud to have six different collaborative workspaces, including three conference rooms, and two dedicated kitchen areas for EnviroForensics’ 75 team members to both work and enjoy each other’s company.

The North Meridian Neighborhood was slowly on the rise before we moved to our renovated office in August of 2016. The popular Indianapolis Cultural Trail is headquartered here, the popular Indianapolis Canal Walk is available for lunch time strolls, employees can grab a drink after work at Brew Link Brewing Company, luxury apartments are right across the street, and Myriad Fitness, a crossfit gym, is within a short walk. And, coming in late 2018, there will be an added infusion of culture with the renowned Phoenix Theater moving its operations to a new 20,000 square feet, state-of-the-art facility nestled at the corner of Illinois street and the Cultural Trail. We’re excited about the future, and hope that our contribution of keeping high-paying jobs in the area helps spur the continual redevelopment of downtown Indianapolis.

Contact us today to learn more about how EnviroForensics can help you develop Brownfields

With over 30 years of experience, Steve Henshaw, PG has a wide range of experience in the environmental remediation field. As CEO of EnviroForensics, Henshaw serves as a client and technical manager on projects associated with site characterization, remedial design, remedial implementation and operation, litigation support and insurance coverage matters. These projects have included landfills, solvent and petroleum refineries, metal plating shops, food processors, chemical manufacturers and distributors, heavy equipment manufacturers, and transporters. Henshaw’s expertise includes knowledge of industry practices and procedures, and an extensive understanding of contaminants in soil and groundwater. He has also served as a testifying expert on behalf of individual landowners and facility operators at several Brownfields sites impacted by industrial activities.

With over 30 years of experience, Steve Henshaw, PG has a wide range of experience in the environmental remediation field. As CEO of EnviroForensics, Henshaw serves as a client and technical manager on projects associated with site characterization, remedial design, remedial implementation and operation, litigation support and insurance coverage matters. These projects have included landfills, solvent and petroleum refineries, metal plating shops, food processors, chemical manufacturers and distributors, heavy equipment manufacturers, and transporters. Henshaw’s expertise includes knowledge of industry practices and procedures, and an extensive understanding of contaminants in soil and groundwater. He has also served as a testifying expert on behalf of individual landowners and facility operators at several Brownfields sites impacted by industrial activities.