AN OVERVIEW OF THE INSURANCE ARCHEOLOGY PROCESS AND THE NUANCES THAT ENVIRONMENTAL ATTORNEYS CONSIDER WHEN DETERMINING WHAT YOUR HISTORICAL INSURANCE SHOULD PAY FOR

BY: DRU SHIELDS, ANDREW SKWIERAWSKI, TED WARPANSKI

Unearthing old insurance coverage during an insurance archeology search can trigger a feeling of immense relief for a drycleaner or small business owner looking for financial assistance to cover their environmental services. It is, however, the first step in a series of steps towards getting those critical funds. Grappling with the language of the policy and the state-by-state caselaw which dictates what the insurance carriers are obligated to pay out will help set reasonable expectations and help you chart out your larger environmental cleanup plans.

With the inherent complexities of insurance archeology and claims tendering activities, it is always recommended that you have experts by your side through this undertaking. This article will give you a basic understanding of how an experienced insurance archeologist combined with a skilled attorney with experience in insurance law, can find your old coverage and use it to pay for defense against environmental claims.

Watch the webinar “How much environmental cleanup will your insurance actually pay for?”

HOW TO FIND OLD INSURANCE COVERAGE

The sole purpose of understanding how much environmental cleanup your insurance carrier will cover depends on finding those old policies first. When we are approached by drycleaners who are facing environmental contamination issues, we prioritize looking into insurance as a means of funding environmental investigation and remediation. This is the case, no matter what part of the process a drycleaner is in. It is possible that they just found out that they have an issue, or they are getting their ducks in a row and are looking to be proactive, or they are in the middle of addressing environmental concerns. Once that can of worms has been opened, it is nearly impossible to close it again. The goal is to minimize out-of-pocket expenses because environmental cleanup is expensive.

Through historical insurance archeology we reconstruct your historical insurance coverage or your predecessor’s historical insurance coverage. The definition of insurance archeology is tracking down the proof that policies existed. We want to know the terms and conditions, the limits of those policies, and many times we do not find full policies, but we need formal proof of their existence. This could be through canceled checks, declaration pages or cancellation notices. In those instances, when we do not have a full policy, but we have secondary proof like this, we usually partner that proof with specimen policies to back up those existing pieces. We look for Commercial General Liability (CGL) policies, which are your standard slip-and-fall policies that would have protected the policyholder against claims for property or bodily damage.

When it comes to finding your historical insurance policies, it is a common misconception that there is some sort of database or website where insurance archeologists just type in a person’s information, and it will pull up that person’s historical information. Unfortunately, that is not the case. If it were, insurance archeology services probably would not exist. Many times, the first step to reconstructing your insurance coverage is by reviewing a business owner’s old business files and old personal files. We always recommend that a business owner holds onto everything they have. Information held within old business records—no matter how inconsequential they seem to you—could hold information that an insurance archeologist is going to find valuable in their search from tracking down leads to coverage.

That said, it is common for a drycleaner to throw out all their old records, and in these cases an insurance archeologist is going to dig deeper. Insurance archeologists look everywhere for proof of insurance, and it usually is a bit more involved than digging through old files. They conduct personal interviews, review public records, and review any available business records to look for leads in addition to proprietary methods. Understanding the full scope of coverage available to a business is really the first key to understanding how much environmental cleanup is going to be covered by insurance.

RECONSTRUCTING OLD INSURANCE COVERAGE TO TENDER A CLAIM

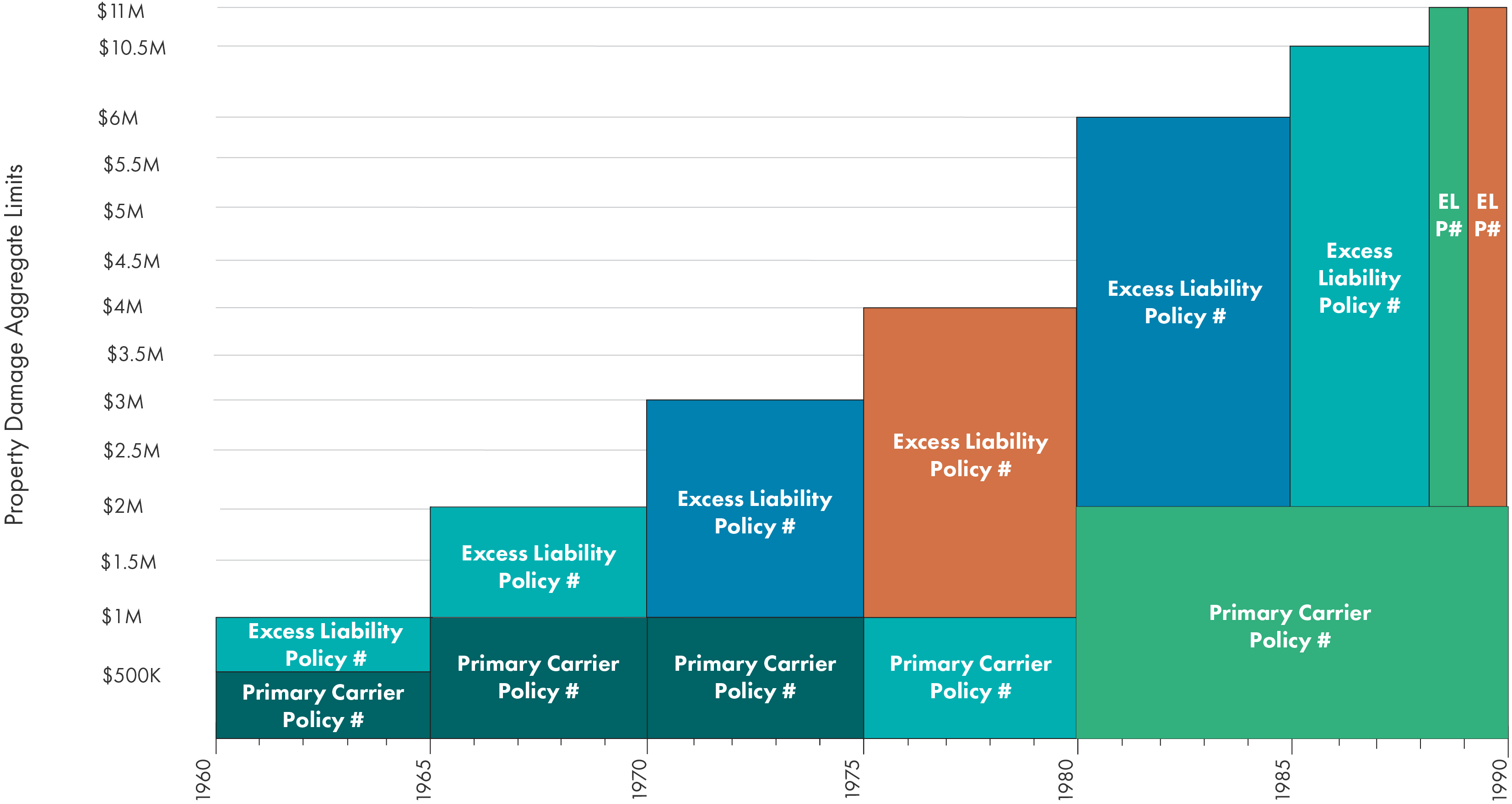

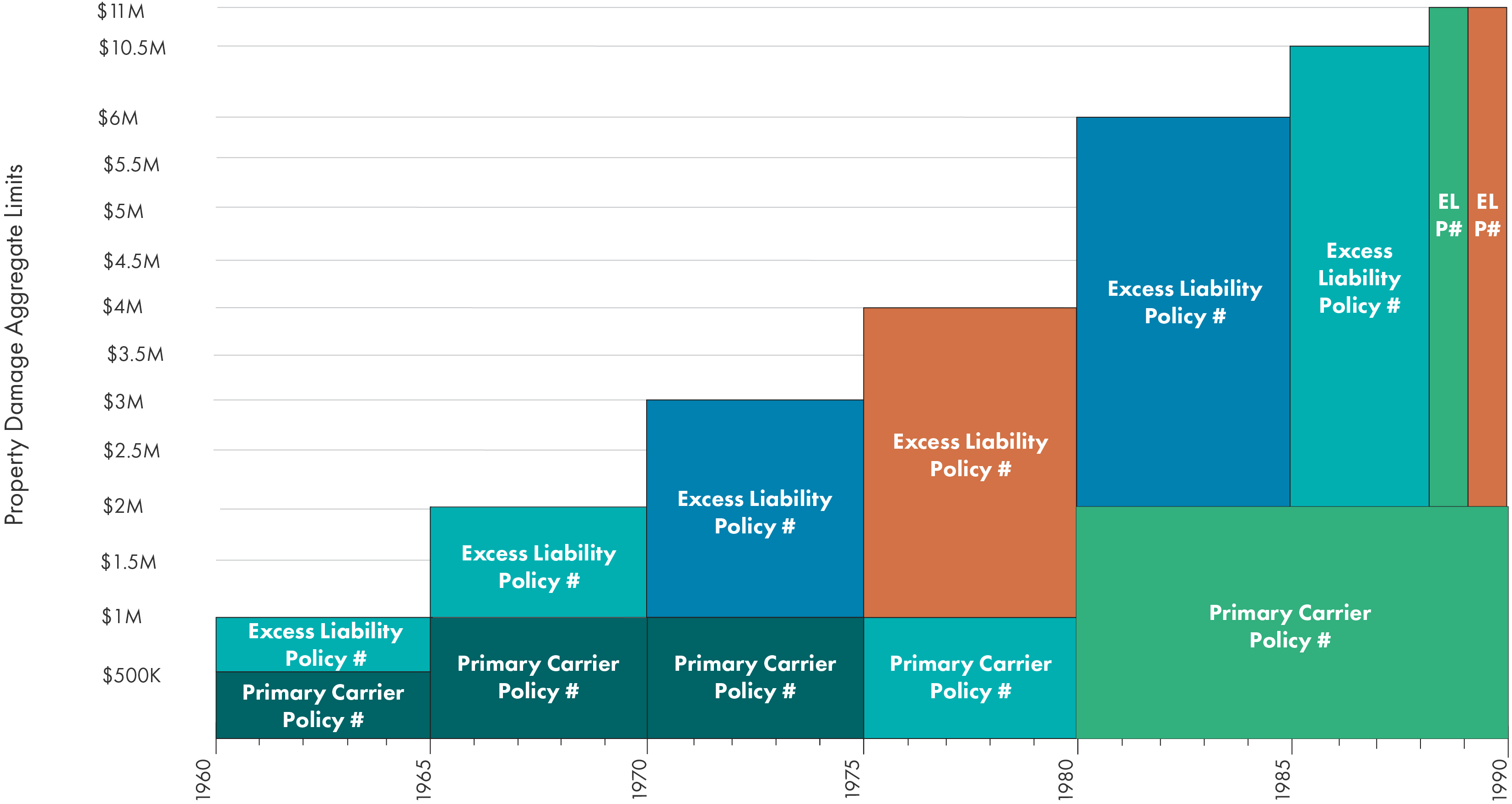

At the end of the insurance archeology process, we produce a comprehensive coverage chart with the available evidence from the search. In an ideal situation, the coverage chart will look something like this:

In this example chart, the client has provided the insurance archeologist with evidence of 30 years of continuous coverage at both the primary and excess level. It is generally more typical to find evidence of coverage for just a year or two with lower primary limits under $1 million to under $500k level. As these policies aggregate over the coverage period, that is enough to pay for some environmental cleanups. However, even if you can only unearth evidence of coverage for a year and at a lower limit, any dollar that the insurer would fund a cleanup is a dollar saved from the responsible party’s pocket.

Once we trigger historical Commercial General Liability (CGL) coverage, there is a variety of tasks that insurance can cover. “CGL coverage for cleanup” is probably the phrase that brought you here to this blog post, but cleanup also includes environmental investigation tasks and technical fieldwork to determine the nature and extent of the problem in the soil and/or groundwater. Cleanup tasks that are part of the regulatory closure process under the umbrella of “environmental cleanup” can be paid for using CGL policies. That list includes:

Interfacing with the regulator

It’s not a one-and-done meeting or letter. In many cases, this “interfacing” includes reports, negotiations, and agreements with a regulatory body that can last for years.

Responsible Party Search

If there was a prior owner-operator at the facility or there is an off-site contributor to a larger contaminant plume, they can be compelled to shoulder some of the environmental liability.

Legal Defense

Legal fees that go into defending a responsible party against a regulatory claim or a third-party claim.

It takes a trained eye to look at an insurance policy, but more importantly, to resolve the differences in interpretation. Differences in interpretation are where experts on your team come in to discuss the coverage aspect of that actual policy contract. The coverage/interpretation of those contracts varies from state to state. Several defenses can be raised by an insurer, so it takes a trained eye to interpret and to resolve those differences.

INTERPRETING OLD INSURANCE POLICIES TO DETERMINE COVERAGE

There are the fundamental questions that you must ask on any claim to determine the likelihood of coverage:

- What are the risks that you want to litigate coverage on?

- What do you think you are going to get at the end of the day?

The starting point on all these projects is the “insuring language” in the policy, which is normally some variation of the following:

The insurer is obligated to pay on behalf of the insured all sums which the insured will become legally obligated to pay as damages because of property damage to which the insurance applies caused by an occurrence, and the Insurer shall have the right and duty to defend the insured against any suit seeking damages, even if the allegations in the suit are groundless.

Within that language, we focus on how the following key terms are interpreted:

WHAT DOES “AS DAMAGES” AND “PROPERTY DAMAGE” MEAN?

Courts differ in jurisdictions as to whether government demands to conduct environmental investigations and cleanups are considered “damages.” There are older cases that have characterized a government demand as a request for injunctive relief against the insured versus a claim for damages. Some courts have found that government demand letters are not “damages.” However, more courts are finding that damages of the environmental cleanup costs themselves are “damages” as an impairment or a liability. They broadly construe that language to cover environmental cleanup costs. That said, the jurisdiction where you are is a particularly important variable in figuring out if you are covered for the claim that is being made against you.

WHAT IS “AN OCCURRENCE”?

There are two types of General Liability policies: “occurrence-based” policies and “claims-made” policies. The latter of which does not really help you in this instance because “Claims-made” policies require that you make the claim within the policy period. So, that means that if you have a policy from 1980-1981, you need to have made the claim to your insurance carrier between 1980 and 1981. The majority of older CGL policies are “occurrence-based,” which means there must be something that happened during the policy period that gave rise to potential damages and potential liability. The trouble is in an environmental context, we do not often have an acute incident that we can point to and say, “that happened then,” although sometimes we do. Sometimes there are recorded spills like, for example, your perc supply company came to your store in 1981 and did not attach the hose right. It fell off as it was filling, and 15 gallons of perc came onto your driveway. It will raise the question of when the occurrence happened so it can become more central to the litigation.

Occurrence-based policies under the “Continuous Trigger Doctrine”

If you bought your drycleaner in 1975, but there was a drycleaner there from 1965 to 1975 operated by someone else, and it’s likely that there was some contamination that occurred before you got there, you can still make an argument that your 1975-1977 policy may be on the hook under the “continuous trigger” doctrine. What that doctrine says is instead of defining an occurrence as a limited specific act that occurred at one point in time, the damage the contaminant has done continues through the entire period that it is present in the ground: the soil and the groundwater. That contamination constitutes one trigger that can span multiple policy periods, which is helpful to drycleaners for getting coverage because you do not have to point to one specific occurrence. If we can prove contamination existed prior to a policy period, and nothing was done to clean it up, under the continuous trigger doctrine there is a particularly good argument that there has been an occurrence during the policy period. So, if you start from where you think the first release happened and work back to the point where some sort of cleanup occurs, there is a good argument that there is an occurrence, and the policies throughout that period become triggered.

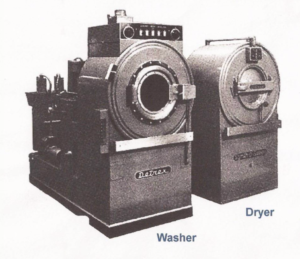

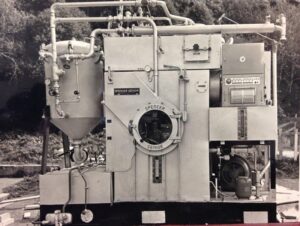

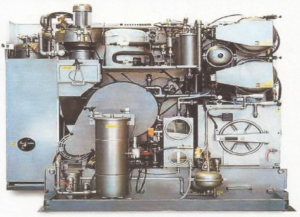

Therefore, one of the first things we look for is if there were any first-generation drycleaning machines used on the property. Transfer machines have an inherent opportunity for drips and dribbles and little amounts of drycleaning solution to fall off and hit the concrete floor and move through. It is understood by the insurance carriers that first-generation drycleaning machines operating with perc were likely to have caused contamination. Insurance carriers sort of tacitly acknowledge the fact that these machines were not as tight as they needed to be. When we started to get the third-generation machines with the dry-to-dry functionality and a pan underneath it, that made a significant difference into whether there was a likelihood that contamination occurred. So, if you cannot pinpoint the occurrence, you can often at least point to when there was a first-generation machine in use which will help in making the argument to the insurance carrier that there was an occurrence and property damage during that policy period.

WHAT IS THE SCOPE OF THE INSURER’S OBLIGATION OR “DUTY TO DEFEND ANY SUIT SEEKING DAMAGES”, WHICH INCLUDES WHAT IS A “SUIT SEEKING DAMAGES”?

Does a responsible party letter constitute a suit? In many of these cases, there is not an actual lawsuit by a neighbor or a third party making a claim against the drycleaner to recover their own costs. It is normally either the drycleaner discovering the contamination themselves or it is discovered some other way, in the “right of way” during municipal work or during a property transaction. When that information is discovered, there is an obligation on behalf of the property owner to report that to their state agency. The state agency, or sometimes the federal government, will issue a “responsible party letter” to that entity saying, “you are obligated to investigate and remediate this site within accordance with your state regulations and statutes.”

The question that needs to be answered after receiving this letter is whether it is the functional equivalent of a suit in that state, which will determine the scope of coverage. Some states where this meets that standard are Maryland, Arizona, Wisconsin, Alabama, Minnesota, New Jersey*, and Indiana. However, most states have interpretation of the law where a responsible party letter constitutes a suit because it does have real consequences for the insured. So, that may trigger the obligation to defend on behalf of the insured to defend that lawsuit or that claim.

What is the duty to defend? Think about a car accident where you rear-end someone at the intersection, and you cause damage or personal injury, and that party sues you. You tell your insurance company and give them notice of the suit and they take over. They activate their panel of defense lawyers that they use to defend against the suit because they know that it is covered underneath the policy. You do not have to pay for the attorney’s fees since it is under the policy.

In the context of a responsible party letter, it is a little more nuanced because the actual defense of the claim is interacting with the regulators on the responsible party’s obligation. You may be looking at what other responsible parties may be out there too. That is why we consider the responsible party letter as the equivalent of a suit and what it provides because there is a duty to indemnify the insured for all sums they are obligated to pay as damages, but there is also a duty to defend them from that claim. The duty to defend itself is broader because you do not actually have to be found liable for anything yet. Your insurance defends you from liability, so it is broader. Even if there is an arguable claim that is made against a party, that duty to defend may kick in, even though ultimately there may be no coverage for a particular component of that claim.

When we look at Duty to Defend, we look at the “Four Corners Rule.” We look at what the policy says and what claim says, and compare those, and if there is any argument in favor of coverage for that claim, that normally triggers the “Duty to Defend.” Therefore, as soon as we get one of these letters or demands, we put the carriers on notice. Typically, the insurer’s obligations do not kick in until they are put on notice. It is the tender to that claim that triggers the duty to defend and starts that process.

ARE THERE ANY EXCLUSIONS?

There is a pollution exclusion in all these policies issued after about 1970. Prior to that time, that exclusion did not exist.

Sudden and Accidental Pollution Exclusion

The insurance carriers decided that they wanted to protect against intentional polluters, so around 1970 they added language in their policies that says, “any release or escape of pollutants isn’t going to be covered, unless that release is ‘sudden and accidental’”.

What constitutes a sudden and accidental release? This is a hotly debated question. Some courts have found that “sudden” implies that there is some time, some temporal immediacy. For example, someone accidentally knocks over a drum. That is a sudden accident. Or the delivery truck’s hose broke. That is a sudden accident. For those examples, it is easy to say there is a clear sudden, temporal component.

Over time, there has been litigation that looked at some of the insurers’ own records that found that their own definition of a sudden and accidental release was the equivalent to an occurrence, so some courts have found “sudden and accidental” to be ambiguous and have ruled in favor of the policyholder.

Absolute Pollution Exclusion

Around 1986, the insurance companies started to notice the pattern that courts were finding the “sudden and accidental” language ambiguous, so they decided to make their language broader and clearer in what is now called the “absolute pollution exclusion.” This means there is no longer an exception for sudden and accidental releases. Any pollutant that is discharged would be excluded. All states, except Indiana, have found this language to be unambiguous, especially as it applies to a situation like a drycleaner. Indiana found it ambiguous in terms of a pollutant, and for good reason. The insurance companies are saying that what happens in respect to one of the most integral parts of your drycleaning business is not covered under your policy. So far, Indiana is the only state that has taken a broad view and said that the absolute pollution exclusion really does not apply to these types of contamination cases.

Owned Property Exclusion

The “Owned Property Exclusion” says that any damage to a property that you have owned or leased in the past is not going to be covered by insurance. The insurance companies want you to cover your own loss of diminished property value. The scope of this exclusion has been litigated in several courts in several different states. Most have found in favor of the insured in cases where the contamination migrated to groundwater, because the landowner does not own the groundwater. It is owned by the state or held in trust by the state. That is considered damage to other property so that is not going to be excluded.

Similarly, if contamination that started on your property migrated to a neighboring property, that is also considered damage to third-party property, which will not be excluded for coverage. Some states have found preventative measures where a businessowner cleans up their property to prevent damage to another property to be within the exclusion, while some may allow for that to still be covered as a part of the cleanup costs. If the government is requiring you to clean up your property to restore the environment, some courts have considered “the environment” to be the damage in general, and since states have the right to compel you to undertake that investigation and cleanup, that has been found to not be excluded for coverage.

We have not seen vapor intrusion directly litigated under the owned property exclusion yet, and we have not had conversations with insurers about that issue and risk. However, if you keep in mind that vapor intrusion is another component of damage to the environment you must remedy as a responsible party, you may have a convincing case for coverage.

DEFENSES TO COVERAGE – LATE NOTICE AND PREJUDICE

After figuring all of this out:

- If there is an initial grant of coverage under the language

- If there was a claim

- If there was damage

- If there was a suit

- If there were any exclusions that would prevent coverage

…and you have an RP Letter in an authority where it is considered a suit, your next step is to figure out if the insurance carrier has any other defenses based upon either the language or the caselaw that can allow the insurer to potentially get out of covering you. In almost every one of these cases, the primary defense they have is “Late Notice and Prejudice.”

A good example of this is if damage happened in 1975, and it was found when you sold the property in 2015, that may be considered untimely notice. If the tender of the claim is late and lateness varies by authority, the insurer may try to get out. There is a statutory definition in a lot of jurisdictions that says if any claim is tendered to the insurance carrier more than two years after the occurrence (or another specified deadline), the insurance carrier can say that it is “late.” Some jurisdictions will hold that if the tender of the claim is “late,” by the statutory definition or within the contract, that is a complete bar to making a claim.

Most jurisdictions take a slightly different interpretation to “late notice.” In most cases, if the tender is late, you can still make the claim, but it is now the insured’s obligation to convince the court that there has been no prejudice against the insurance carrier’s rights because of the notice being late. To explain prejudice, we will use a car accident as an example. After a car accident, if you do not tell the insurance carrier about the accident, the scene gets cleaned up, nobody took pictures, and you did not get all the witnesses’ information, the insurance carrier’s ability to investigate what happened is prejudiced. They do not have the ability to make a good coverage determination because of lost information and the failure to give them notice in time for them to do their investigation.

But that standard issue of prejudice does not apply with the same force when it comes to environmental contamination because we know that the contamination may have occurred long before the insured was even made aware of it. When that happens, the ability to investigate was not there at the time of the occurrence, because the owner did not know that the contamination was there. Then, there is the question of when the insured got notice of the contamination — which is normally during a real estate transaction—when the insured did their own investigation of the contamination, and when they put the insurance carrier on notice.

That is a more crucial potential period for “prejudice” because, during that time, the plume is migrating with the property owner’s knowledge. Was the insurance carrier and their failure to get notice an impediment to investigating and potentially remediating the extent of the contamination? And did the contamination get worse over the course of that period? If during that period between discovering the contamination and tendering the claim to the carriers, you were working with regulators and an environmental consultant to investigate and remediate the contamination, the insurance carrier has a solid argument that they were prejudiced. Therefore, you should always put the carriers on notice quickly. The insurance carrier’s claim that they were prejudiced is going to ring hollow if you put them on notice at the beginning of this process.

Another important piece of this is the costs that you incurred for the investigation prior to tender of the insurance carrier are not recoverable. This means the longer you wait to put your insurance carrier on notice the bigger the expense that cannot be recovered. It is not completely impossible to recover these costs, but it is difficult. Most insurance carriers will say, “anything that occurred pre-tender—before you gave us notice – no chance.” That applies in respect to anything that falls within the scope of the “duty to defend.” If it is work that is done pre-tender, you really must make a good argument that it is part of the carrier’s “duty to indemnify,” and to reimburse you for that loss.

DEFENSE VS. INDEMNITY

What is Defense vs. Indemnity? The big issue is not paying the attorney’s fees. This is well understood as being part of the defense cost. It is whether the consultant’s costs to do the investigation of the site are covered by the policy as a part of the “duty to defend.” The reason this distinction is important is that the “duty to defend” is uncapped. There is no limit to how much an insurer may have to spend to defend a case. However, there is a limit on how much they would have to indemnify the insured for.

You may have a million dollars in coverage for indemnity, and you also have a duty to defend, so many times, the investigation of a site itself can cost well more than that indemnity limit itself. Are the consulting costs to conduct the investigation part of the defense of the claim or are they a part of the indemnity limits? On one hand, the letter from the regulator says, “investigate this site and then remediate it,” and insurers argue that the investigation is being ordered by the government, so it is part of the indemnity obligation. Some courts have addressed this issue while many have not addressed it, so it is subject to discussion with your insurer in your state as to how they are going to handle it. Getting the consulting costs covered as investigation costs as part of the defense obligation allows you to learn about the environmental conditions of your site. Are there other responsible parties? When did the releases occur? How did they occur? How do you limit the liability that you are going to be obligated to pay for at your site? This is a critical issue in understanding how much coverage you will receive from your policies based on your state.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Duty of Cooperation

You must cooperate with your carrier. If they ask you questions, you must answer them, and you must provide them with information. Otherwise, they can claim that you did not cooperate with them.

Voluntary Assumptions of Liability

Another way of saying this is agreeing to everything before the insurance company is even on notice of the claim because that can be argued as a defense for them as an assumption of liability. This does not include reporting an environmental contamination to your state regulator.

Lost Policies-evidence of insurance

This is a state-by-state consideration of what type of evidence you will need to show to prove coverage of insurance. What constitutes adequate secondary evidence of insurance?

Private causes of action against other responsible parties

Were there other polluters on the property before you? What actions will your team need to take to find these other responsible parties and compel them to share in the liability costs?

Participation in State Cleanup Funds

Some states have cleanup trust funds to help pay for environmental cleanup. Ask your environmental consultants and attorneys how to access these funds while also utilizing your old insurance.

These are all things to think about as you enter this process of finding your old insurance. What we hope you understand is that locating this old coverage should be celebrated, but it is one battle in an even bigger war. Make sure you have experts by your side that can prove the existence of coverage, tender the claim with your insurers, and put together a compelling legal argument based on the language of the policies and your state’s unique interpretation of the law. The extent to which you utilize these resources will play a key role in deciding how much environmental cleanup your insurance will cover.

Learn more about our insurance archeology services.

There is caselaw in New Jersey that the insurance carriers have used to argue that they do not have to pay for “defense” upfront. That has the potential to derail a project because there is a substantial difference between fronting the money for environmental investigation for the defense of a claim versus having the insurance carrier pay for it upfront. Getting reimbursed at the end after you have fronted what can sometimes be hundreds of thousands of dollars is a lot harder to deal with.

Dru Shields, Director of Drycleaner Accounts

Dru Shields, Director of Drycleaner Accounts

For over 10 years, Dru has helped numerous business and property owners facing regulatory action, navigate and manage their environmental liability. Dru has vast experience in assisting dry cleaners in securing funding for their environmental cleanups through historical insurance policies. Dru is a member of numerous drycleaning associations in addition to serving on the Midwest Drycleaning and Laundry Institute (MWDLI) advisory council and on the Drycleaning & Laundry Institute Board (DLI) as an Allied Trade District Committee Member.

Andrew Skwierawski, Senior Attorney

Andrew Skwierawski, Senior Attorney

Andrew Skwierawski has over 12 years of legal experience. He combines that with a background as a veteran software developer and small business owner with his technical and scientific-focused law practice that includes environmental litigation, e-discovery, complex commercial disputes and municipal compliance. Andy’s environmental litigation work for Davis|Kuelthau has included representing manufacturers, property owners, farmers and environmental organizations. Andy represents drycleaners at dozens of sites across the State to address historical site contamination with the Wisconsin DNR as well as resolving insurance coverage disputes with their insurers.

Ted Warpinski, Shareholder

Ted Warpinski, Shareholder

Ted Warpinski has over 30 years of experience working on a wide variety of environmental and litigation cases across Wisconsin. From the early years of Superfund litigation on sites like the Fadrowski Drum Disposal Site in Franklin, Wisconsin and the Moss-American Site in Milwaukee, Ted has been immersed in both the legal and technical aspects of environmental law. Ted’s litigation practice has grown to include environmental nuisance claims and toxic tort litigation, contract and property disputes, construction defects, insurance coverage litigation and enforcement actions. Ted also works very closely with the firm’s real estate and development lawyers handling due diligence investigations and environmental permitting. His experience includes addressing real estate deals that involve brownfield issues, where the risk of liability for historical contamination is a major consideration. Ted’s experience allows him to assist the Davis|Kuelthau team with understanding and managing these risks.

Andrew Skwierawski, Senior Attorney

Andrew Skwierawski, Senior Attorney Ted Warpinski, Shareholder

Ted Warpinski, Shareholder